Modular Arithmetic

Division

- For every integer dividend

nand divisorm ≠ 0, there exists unique quotientqand remainderrsuch that.

- If r is the remainder after dividing

nbym, we writen mod m = r

\[if \quad n = 14 \quad \textrm{and} \quad m = 6\] \[q = 14 \:/ \:6 = 2 \quad and \quad \:r \:= \:14 \:\% \:6 \:= \:2\]An example showing.

Note.

C++ % operator is the same as mod only for positive dividends

For negative dividends, % operator returns negative remainder (try it)

- Reason: silly design, integer division, and requirement that

To fix this, we need to add m at the end

To avoid needing to deal with positive and negative dividends differently, just always add m and take mod m afterwards

1

2

3

4

5

int mod(int a, int m) {

return (a % m + m) % m;

}

An example showing.

1

2

-3 % 10 = -3

(-3 + 10 ) % 10 = 7

Modular Addition

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

int mod_add(int a, int b, int m) {

return mod(mod(a, m) + mod(b, m), m);

// assuming a + b does not overflow

// return (a + b) % m;

}

Modular Subtraction

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

int mod_sub(int a, int b, int m) {

return mod(mod(a, m) - mod(b, m), m);

// assuming assuming a - b does not overflow

// return mod(a – b, m);

}

Modular Multiplication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

int mod_mul(int a, int b, int m) {

return mod(mod(a, m) * mod(b, m), m);

// assuming a * b does not overflow

// return (a * b) % m;

}

Divisibility, Primes

Divisibility

- Integer $d$ divides integer $n$ if there is a $k$ such that $dk = n$

- $d$ is a divisor or factor of $n$

- $n$ is a multiple of $d$

- $n$ is divisible by $d$

- We write this as

d | n - Theorem:

d | nif and only ifn ≡ 0 (mod d) - Easy code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

if(n % d == 0) {

// n is divisible by d

k = n / d;

}

Note.

- By our definition

0is divisible by any integer- No integer is divisible by

0, except… 0is divisible by0

- However, in practice, using the % operator with 0 right operand causes programs to crash (division by zero error)

Primes

- An integer

n > 1is prime if the only integers dividing it are1 and n - Otherwise it is composite

- Integers

≤ 1are considered neither prime nor composite

Primality Testing

- Easy way: look for a divisor between

2 and n − 1 - This is $O(n)$ time

- Theorem: If $n$ is composite, then it has a divisor ≤ $\sqrt{n}$

- Proof: If $ab = n$ and $ a > \sqrt{n}$ then $ \frac{1}{a} < \frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}$

- Means, we only need to test $O(\sqrt{n})$ integers for divisibility

Primality Testing by Trial Division in $O(\sqrt{n})$

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

bool is_prime(long long n) {

bool ans = true;

for(long long i = 2; i * i <= n; i++)

if(n % i == 0)

ans = false;

return ans;

}

Multiple Query Primality Testing

- Answer $q$ queries of the form: is $n$ prime?

- Constraints

- $q ≤ 10^7 $

- $n ≤ 10^6 $

- Answer each query by trial division ⇒ $O(q\sqrt{n})$ which is too slow

- Goal: precompute answers so that we can answer each query in $O(1)$

Sieve of Eratosthenes

- Idea: for any integer $i ≥ 2$, ki is composite for all $k > 1$

- Initially assume all integers are prime

- Go through all integers and and mark all of their multiples (not equal to themselves) composite

- Theorem: The numbers that are not marked are prime

- Proof: If $p$ is not marked, then there is no $k > 1$ and i between 2 and p where $ki = p$

Sieve of Eratosthenes c++ code

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

bool is_prime[MAX_N+1];

void sieve(int n) {

is_prime[0] = is_prime[1] = false;

for(int i = 2; i <= n; i++)

is_prime[i] = true;

for(int i = 2; i <= n; i++)

for(int k = 2; k * i <= n; k++)

is_prime[k * i] = false;

}

Sieve of Eratosthenes: Analysis

Double nested for loop appears to be $O(n^2);$ however…

Only $ \frac{n}{i} + C$ multiples for iteration $i$

The sum $\sum_{i=2}^n \frac{i}{i}$ is called the harmonic series

Bounds for the harmonic series

\(\sum_{i=2}^n \frac{i}{i} = \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} +\frac{1}{4} +\frac{1}{5} +\frac{1}{6} +\frac{1}{7} +\frac{1}{8} +\frac{1}{9} +\frac{1}{10} +\frac{1}{11} +\frac{1}{12} +\frac{1}{13} +\frac{1}{14} +\frac{1}{15}\) \(\: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: < \frac{1}{2} +\frac{1}{2} +\frac{1}{4} +\frac{1}{4} +\frac{1}{4} +\frac{1}{4} +\frac{1}{8} +\frac{1}{8} +\frac{1}{8} +\frac{1}{8}+\frac{1}{8}+\frac{1}{8}+\frac{1}{8}+\frac{1}{8}\)

\[= \log_2 n\](the number of powers of two up to n)

A Minor Speedup

- Notice that when we reach some composite number i, all its multiples are already crossed out

- For all integers ki, if p divides i, then p also divides ki

- Only mark multiples of prime numbers

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

bool is_prime[MAX_N+1];

void sieve(int n) {

is_prime[0] = is_prime[1] = false;

for(int i = 2; i <= n; i++)

is_prime[i] = true;

for(int i = 2; i <= n; i++)

if(is_prime[i])

for(int k = 2; k * i <= n; k++)

is_prime[k * i] = false;

}

Practice Problems

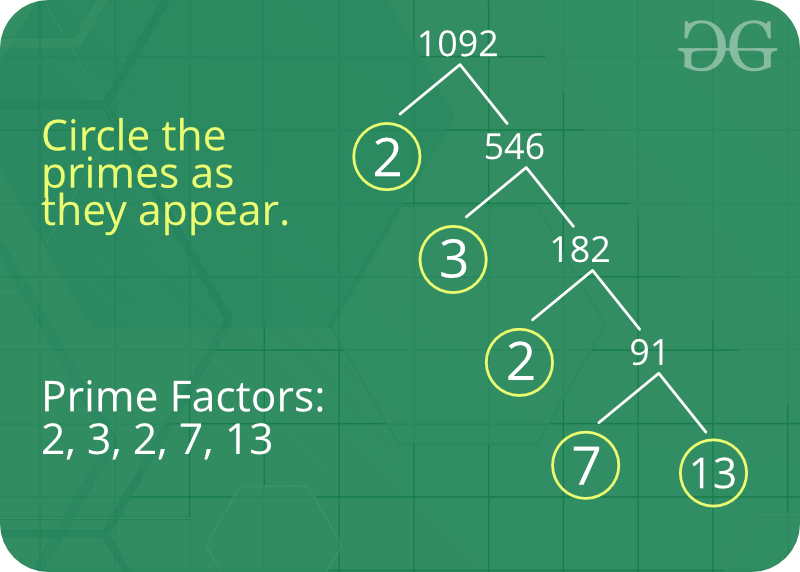

Prime Factor

Prime factor is the factor of the given number which is a prime number. Factors are the numbers you multiply together to get another number. In simple words, prime factor is finding which prime numbers multiply together to make the original number.

Example: The prime factors of 15 are 3 and 5 (because 3×5=15, and 3 and 5 are prime numbers).

Some interesting fact about Prime Factor :

- There is only one (unique!) set of prime factors for any number.

- In order to maintain this property of unique prime factorizations, it is necessary that the number one, 1, be categorized as neither prime nor composite.

- Prime factorizations can help us with divisibility, simplifying fractions, and finding common denominators for fractions.

- Pollard’s Rho is a prime factorization algorithm, particularly fast for a large composite number with small prime factors.

- Cryptography is the study of secret codes. Prime Factorization is very important to people who try to make (or break) secret codes based on numbers.

How to print a prime factor of a number?

solution:

Given a number n, write a function to print all prime factors of n. For example, if the input number is 12, then output should be “2 2 3” and if the input number is 315, then output should be “3 3 5 7”.

Following are the steps to find all prime factors:

- While n is divisible by 2, print 2 and divide n by 2.

- After step 1, n must be odd. Now start a loop from i = 3 to square root of n. While i divides n, print i and divide n by i, increment i by 2 and continue.

- If n is a prime number and is greater than 2, then n will not become 1 by above two steps. So print n if it is greater than 2.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

// Program to print all prime factors

# include <stdio.h>

# include <math.h>

// A function to print all prime factors of a given number n

void primeFactors(int n)

{

// Print the number of 2s that divide n

while (n%2 == 0)

{

printf("%d ", 2);

n = n/2;

}

// n must be odd at this point. So we can skip

// one element (Note i = i +2)

for (int i = 3; i <= sqrt(n); i = i+2)

{

// While i divides n, print i and divide n

while (n%i == 0)

{

printf("%d ", i);

n = n/i;

}

}

// This condition is to handle the case when n

// is a prime number greater than 2

if (n > 2)

printf ("%d ", n);

}

/* Driver program to test above function */

int main()

{

int n = 315;

primeFactors(n);

return 0;

}

Euclidean algorithm for computing the greatest common divisor

Given two non-negative integers $a$ and $b$, we have to find their GCD (greatest common divisor), i.e. the largest number which is a divisor of both $a$ and $b$. It’s commonly denoted by $\gcd(a, b)$. Mathematically it is defined as:

\[\gcd(a, b) = \max \{k > 0 : (k \mid a) \text{ and } (k \mid b) \}\](here the symbol “$\mid$” denotes divisibility, i.e. “$k \mid a$” means “$k$ divides $a$”)

When one of the numbers is zero, while the other is non-zero, their greatest common divisor, by definition, is the second number. When both numbers are zero, their greatest common divisor is undefined (it can be any arbitrarily large number), but it is convenient to define it as zero as well to preserve the associativity of $\gcd$. Which gives us a simple rule: if one of the numbers is zero, the greatest common divisor is the other number.

The Euclidean algorithm, discussed below, allows to find the greatest common divisor of two numbers $a$ and $b$ in $O(\log \min(a, b))$.

The algorithm was first described in Euclid’s “Elements” (circa 300 BC), but it is possible that the algorithm has even earlier origins.

Algorithm

Originally, the Euclidean algorithm was formulated as follows: subtract the smaller number from the larger one until one of the numbers is zero. Indeed, if $g$ divides $a$ and $b$, it also divides $a-b$. On the other hand, if $g$ divides $a-b$ and $b$, then it also divides $a = b + (a-b)$, which means that the sets of the common divisors of ${a, b}$ and ${b,a-b}$ coincide.

Note that $a$ remains the larger number until $b$ is subtracted from it at least $\left\lfloor\frac{a}{b}\right\rfloor$ times. Therefore, to speed things up, $a-b$ is substituted with $a-\left\lfloor\frac{a}{b}\right\rfloor b = a \bmod b$. Then the algorithm is formulated in an extremely simple way:

\[\gcd(a, b) = \begin{cases}a,&\text{if }b = 0 \\ \gcd(b, a \bmod b),&\text{otherwise.}\end{cases}\]Implementation

1

2

3

4

5

6

int gcd (int a, int b) {

if (b == 0)

return a;

else

return gcd (b, a % b);

}

Using the ternary operator in C++, we can write it as a one-liner.

1

2

3

int gcd (int a, int b) {

return b ? gcd (b, a % b) : a;

}

And finally, here is a non-recursive implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

int gcd (int a, int b) {

while (b) {

a %= b;

swap(a, b);

}

return a;

}

Note that since C++17, gcd is implemented as a standard function in C++.

Time Complexity

The running time of the algorithm is estimated by Lamé’s theorem, which establishes a surprising connection between the Euclidean algorithm and the Fibonacci sequence:

If $a > b \geq 1$ and $b < F_n$ for some $n$, the Euclidean algorithm performs at most $n-2$ recursive calls.

Moreover, it is possible to show that the upper bound of this theorem is optimal. When $a = F_n$ and $b = F_{n-1}$, $gcd(a, b)$ will perform exactly $n-2$ recursive calls. In other words, consecutive Fibonacci numbers are the worst case input for Euclid’s algorithm.

Given that Fibonacci numbers grow exponentially, we get that the Euclidean algorithm works in $O(\log \min(a, b))$.

Another way to estimate the complexity is to notice that $a \bmod b$ for the case $a \geq b$ is at least $2$ times smaller than $a$, so the larger number is reduced at least in half on each iteration of the algorithm.

Least common multiple

Calculating the least common multiple (commonly denoted LCM) can be reduced to calculating the GCD with the following simple formula:

\[\text{lcm}(a, b) = \frac{a \cdot b}{\gcd(a, b)}\]Thus, LCM can be calculated using the Euclidean algorithm with the same time complexity:

A possible implementation, that cleverly avoids integer overflows by first dividing $a$ with the GCD, is given here:

1

2

3

int lcm (int a, int b) {

return a / gcd(a, b) * b;

}